Fadel Abdulghany

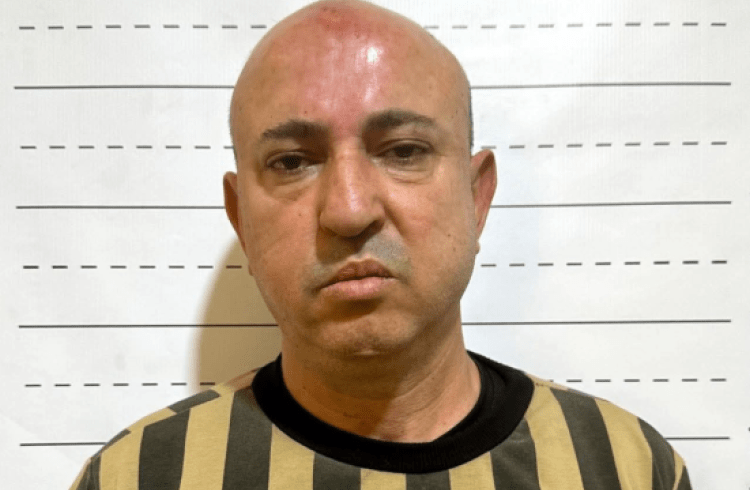

The arrest of Wassim al-Assad on June 21, 2025, marks a significant milestone in Syria’s post-conflict transitional path and signals a level of seriousness on the part of the transitional authorities in dismantling the networks of impunity that have entrenched five decades of authoritarian rule. As the first member of the Assad family to be arrested since the regime’s collapse in December 2024, this arrest has dimensions that go beyond its immediate legal ramifications. It carries profound symbolic significance, given that Wassim al-Assad represented the intersection of family privilege, economic exploitation, and criminal enterprises.

Within the theoretical framework of transitional justice, this event must be understood within a multidimensional analytical approach. Transitional justice, as formulated in post-conflict contexts, encompasses a range of judicial and non-judicial mechanisms designed to address the heavy legacy of gross human rights violations while enabling societal transformation. Wassim al-Assad’s detention exemplifies retributive justice—holding perpetrators accountable for specific crimes—while simultaneously serving as a means of institutionalizing the new political authority in Syria.

The Institutional Dimension of Wassim al-Assad’s Arrest

Transitional justice is practiced in post-authoritarian contexts through a complex interplay of legal, political, and social mechanisms aimed at addressing systematic violations while promoting the transition to democracy. The theoretical framework, as developed by scholars in the field of political transition, recognizes that justice in these contexts serves multiple, sometimes overlapping, objectives: accountability for past crimes, legitimizing the new political order, reconciling divided groups, and establishing institutional safeguards to prevent future violations.

The role of high-profile prosecutions in establishing the legitimacy of new governance structures is a pivotal element of transitional justice theory. These prosecutions produce what some political theorists describe as a “showcase effect,” signaling the new regime’s commitment to the rule of law. In the Syrian context, the arrest of a prominent figure from the Assad family exemplifies what expert Ruti Teitel calls “transitional criminal justice,” whereby individual accountability contributes to the success of the broader political transition. This justice operates on two complementary levels: on the material side, it contributes to dismantling networks of impunity; and on the symbolic side, it affirms that an individual’s political position no longer guarantees immunity from legal consequences. Hence, the success of the new authorities in arresting and prosecuting regime figures becomes a benchmark of their institutional maturity and political capacity.

Wassim al-Assad embodies the trinity that formed the foundation of the former regime’s authority: family privileges that shield individuals from the law, the economic exploitation of state resources and their diversion for private gain, and criminal enterprises in which state institutions merged with organized crime networks. His involvement in the Captagon trade (a drug industry that generated billions of dollars in profits for the Assad regime) stands out as a stark example of what is known in crime literature as “state criminalization,” whereby governing institutions become indistinguishable from criminal organizations. From a transitional justice perspective, the importance of prosecuting such individuals goes beyond their individual criminal acts, but also extends to addressing systemic corruption within state institutions. This aligns with recent trends in transitional justice, which emphasize the need to address economic crimes and corruption as two essential pillars of post-conflict accountability.

Dismantling the Crime Economy

Wassim al-Assad’s arrest is a catalyst for the systematic dismantling of the Captagon networks, which constituted a key pillar of the Assad regime’s political economy. These illicit financial structures represented what is known in the literature of state crime as “narcogovernance”—the integration of the drug trade into the state structure to create self-sustaining instruments of authoritarian control. The theoretical significance of this development goes beyond mere law enforcement; it reflects the beginning of a radical restructuring of Syria’s political economy, from one based on criminal activities to one based on legal and institutional rules. The new authorities’ seizure of Captagon production facilities and distribution networks in the months following the collapse of the Assad regime demonstrates a clear institutional commitment to severing the link between the ruling apparatus and organized crime. This trajectory reinforces the transitional justice literature’s emphasis on the economic dimensions of post-conflict transformations, which argues that achieving sustainable peace requires dismantling the economic structures that perpetuate repression and perpetuate conflict.

Building state capacity through successful security operations is a critical (albeit understudied) dimension of transitional justice implementation.

The meticulous operation that led to Wassim al-Assad’s arrest demonstrated the new government’s operational capabilities, including intelligence gathering, coordination between security agencies, and the execution of complex tasks within a legal framework. From an institutional perspective, these operations achieve several goals: they consolidate the state’s monopoly over the use of legitimate force and enhance citizens’ confidence in security institutions. This type of achievement contributes to consolidating what is known in the literature as “performance legitimacy,” meaning the legitimacy that a government derives from its tangible effectiveness, rather than from ideological rhetoric or coercive control.

The synergy between domestic accountability mechanisms and their international counterparts, particularly through the hoped-for cooperation with the International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism for Syria (IIIM), represents an emerging model for a hybrid structure within the transitional justice system. The IIIM’s unprecedented access to Syrian territory following the collapse of the Assad regime enabled the preservation and documentation of evidence, thereby strengthening judicial efforts at both the domestic and international levels. This partnership reflects the principle of “positive complementarity” enshrined in international criminal law, whereby international mechanisms enhance, rather than replace, domestic justice. The uniqueness of this model lies in its voluntary nature, as the state emerging from conflict engages itself in an international partnership to strengthen its accountability processes. This approach represents a qualitative shift that transcends the duality of national sovereignty and international intervention, toward a cooperative framework that leverages the strengths of various institutional actors.

Conclusions

Wassim al-Assad’s arrest embodies a multidimensional phenomenon that goes beyond the mere detention of an individual. Through its symbolic, institutional, and material dimensions, this arrest highlights the complex transformations Syria is undergoing on its path toward justice and accountability after decades of authoritarian rule. Theoretical analysis demonstrates that individual prosecutions can serve as a catalyst for broader transformations, including dismantling criminal networks, building institutional capacity, and establishing new standards of good governance. Thus, this case reveals the interconnectedness of transitional justice mechanisms, which simultaneously pursue retributive, reconciliatory, and transformative goals.

From the perspective of transitional justice studies, the Syrian case provides rich analytical material for understanding the evolution of accountability models in contemporary post-conflict contexts. The voluntary integration of international and local mechanisms challenges traditional models of separation between national and international justice, proposing a cooperative alternative that promotes institutional coherence. The focus on dismantling the economic dimensions of authoritarianism, particularly with regard to the “drug governance” structures represented by the Captagon trade, expands the scope of traditional notions of transitional justice to include systemic economic crime alongside political violence.

In this context, the conceptual framework that views transitional justice as an “ongoing process,” not an endpoint, stands out. Its success must be assessed through gradual progress in establishing accountability standards within society. This requires a thoughtful alignment of justice initiatives, beginning with an independent judiciary, accompanied by sustained international support, and, most importantly, the active engagement of victim communities and civil society organizations, to ensure that justice mechanisms reflect societal needs rather than political tensions.

In this long and complex process, Wassim al-Assad’s arrest represents both an achievement and a challenge. It demonstrates what can be achieved, while also highlighting the extent of work that remains in Syria’s journey to end impunity and achieve effective justice.