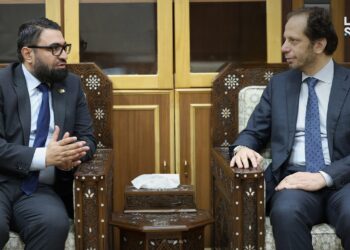

CIVICUS discusses Syria’s political transition and the implications of its new parliament with Fadel Abdulghany, founder and head of the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR). Established in 2011, SNHR documents human rights violations, supports accountability efforts and advocates for justice and democratic reform.

On 5 October, Syria held what authorities called its first parliamentary election since the ousting in December 2024 of Bashar al-Assad, the authoritarian leader who ruled Syria for over two decades. The election’s indirect system allowed around 6,000 electoral college members to select candidates for two-thirds of the 210-seat assembly, with the rest appointed by interim President Ahmed al-Sharaa. Authorities justified the lack of a direct election on the grounds of war displacement and lack of reliable voter rolls, but rights groups warned this gives al-Sharaa effective control over the composition of parliament. In addition, Kurdish-controlled areas in the northeast, Suwayda province and parts of Hasakah and Raqqa were excluded.

Should this be seen as a genuine election?

What happened in Syria shouldn’t really be called an election. It was, in practice, the formation of a legislative council. There was no direct voting by citizens, no open competition and no nationwide participation. The process was organised through an indirect system that selected members of parliament rather than allowing people to elect them.

Of course, there are many difficulties: millions of Syrians are still displaced inside and outside the country, and the institutions needed to hold free and fair elections don’t yet exist. But even with these challenges, the process could have been more representative. It could have included wider consultation, involvement from civil society and participation from different regions and communities. That’s why I see it as a transitional formation of a legislative body, not a democratic election.

How could the process have been more representative?

Even if direct elections were not feasible under current conditions, the process could have been designed to ensure far broader representation. The goal in this phase should have been to build a parliament that reflects the diversity of Syrian society – something more inclusive, participatory and transparent – but that opportunity was missed.

The transitional authorities had alternatives: they could have formed the council through mixed committees combining geographical, professional and social representation. Local community leaders, civil society organisations, professional unions and respected figures from across all regions, including displaced and refugee populations, could have been invited to nominate members.

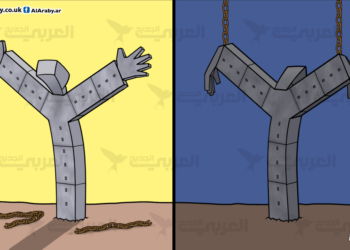

Such a participatory mechanism would have compensated for the absence of direct voting and helped restore confidence in public institutions. Instead, the system relied on a narrow electoral college, largely controlled from the centre, which excluded large portions of society and reinforced perceptions of top-down governance. Civil society’s response reflected this disappointment.

What political path should Syria follow to move toward pluralism and participation?

Full democracy will take time, but right now we can and should aim for a path toward inclusion and pluralism. This means the transition should focus on creating participatory mechanisms: open dialogue among political groups, local representation and an inclusive approach that involves civil society, women, young people and professionals in shaping national priorities. Instead of concentrating power, we need to start sharing it.

We should see this as a gradual process. Over the next two or three years, the government must rebuild institutions, create conditions for displaced people to be able to return and prepare the ground for free elections. If that happens, the next parliament could truly represent people, oversee the drafting of a new constitution and hold the government accountable.

That is how Syria can start moving, step by step, from centralisation toward real political participation.

What powers should the new parliament have to play a genuine role in the transition?

The new parliament must have clear constitutional and supervisory powers. At present, its authority is largely limited to legislative drafting, without mechanisms to question ministers, monitor the executive and ensure accountability. This severely restricts its capacity to influence governance.

To serve as a check on the executive and a platform for national oversight, parliament should be empowered to summon government officials, review policy implementation and oversee public spending. These functions are essential to transparency and rebuilding trust in public institutions.

Further, parliament’s composition must reflect Syria’s demographic and social diversity. Establishing minimum representation for women, minorities and civil society would help legitimise it as a national institution rather than an extension of the interim authority.