Fadel Abdulghany

The collapse of authoritarian regimes poses a significant challenge to societies in their efforts to achieve institutional transformation and justice. In the Syrian context, after more than half a century of Assad regime rule, addressing the legacy of systematic human rights abuses while simultaneously building democratic institutions is a matter of paramount importance. This article proceeds from the premise that removing those implicated in serious human rights violations from state institutions is a legal and moral imperative rooted in the principles of international law and the mechanisms of transitional justice. True transformation requires more than simply changing the regime; it necessitates dismantling the structures that enabled the perpetration of atrocities and rebuilding institutions based on respect for human rights and the rule of law. Without addressing the presence of perpetrators within state structures, the remaining tools of transitional justice lose their effectiveness, rendering the process meaningless and undermining the entire transition process.

The theoretical framework for institutional reform in post-authoritarian contexts begins with recognizing how repressive regimes transform state institutions from protectors of citizens into instruments of repression. The Syrian case is a clear example of the systematic politicization and corruption that have spread throughout most state institutions. The security apparatus has expanded to become an instrument of brutal repression, operating as a direct executive arm. The executive authority has imposed its dominance over the legislative and judicial authorities, stripping the judiciary of its independence and turning it into a political tool for issuing arbitrary rulings and suppressing the opposition.

This structural breakdown of institutional integrity is not limited to the actions of isolated individuals, but encompasses vast networks of complicity. Comparative studies of repressive regimes confirm that their survival depends on systems of collaborators that extend beyond the direct perpetrators of crimes to encompass multiple institutional and social structures. This network of complicity includes elements within the security and military apparatus, judges who legitimized repression through arbitrary rulings, government officials who facilitated violations through administrative procedures, and economic, cultural, and artistic figures who provided symbolic and social support to the regime. This multi-layered complicity generates what can be termed a “social cover” that legitimizes violations and lends them an appearance of acceptance, enabling their continuation.

Transforming institutions requires acknowledging that the violations were not merely the result of isolated individual decisions by regime leaders, but rather the product of a vast system of complicity involving tens of thousands within the state apparatus. Therefore, institutional reform necessitates a comprehensive approach that goes beyond simply holding direct perpetrators accountable; it must also address the infrastructure that enabled the systematic violations. The moral imperative of this reform stems from the recognition that retaining those connected to past abuses in positions of power perpetuates an institutional culture that facilitates further violations, prevents genuine transformation, and threatens the stability of any democratic transition.

International law establishes clear grounds for excluding those implicated in human rights violations from public office, based on the principle of non-recurrence. This principle, which gains particular weight after periods of mass violations, goes beyond simply halting the violations; it obligates states to restructure their institutions in a way that prevents the recurrence of atrocities. Removing those implicated from official positions is a direct application of this obligation, as their continued presence reinforces the institutional culture that initially facilitated the violations.

This legal framework is manifested in a number of international and regional instruments and jurisprudence. The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights requires states to take legislative, constitutional and administrative measures to ensure the implementation of rights and the protection of individuals from violations, while allowing for the imposition of necessary and legitimate restrictions in post-conflict contexts, provided that due process guarantees are respected. Regional judicial bodies have also ruled that states must reorganize their institutions and the structures through which public authority is exercised to ensure full and effective respect for human rights. Furthermore, European human rights jurisprudence has established in landmark cases that “lustration” measures, when carried out with due process guarantees, are consistent with human rights standards and may even be necessary in certain contexts to safeguard democratic systems from the dangers of systemic corruption.

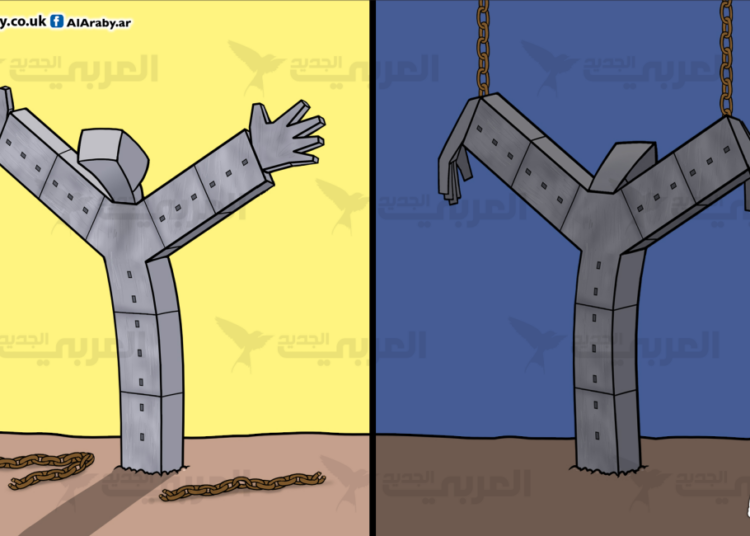

Within the framework of transitional justice, vetting and lustration stand out as two pivotal tools for reforming state institutions. Vetting is an assessment of integrity and functional suitability aimed at ensuring individuals’ eligibility to hold public office in the new system, in accordance with its values and standards. Lustration, derived from “lustratio,” aims to purge institutions of the legacy of authoritarianism by removing those who entrenched its repressive culture. These two mechanisms serve complementary goals: restoring public trust by removing those implicated, transforming abusive institutions into national entities that protect rights, dismantling the structures that enabled the crimes, and preventing a return to authoritarianism in new forms.

Distinguishing between scrutiny and criminal prosecution is crucial to understanding the comprehensiveness of institutional reform. Scrutiny is an administrative/political procedure that does not aim to impose criminal penalties but rather focuses on the ethical and functional suitability for holding public office. This distinction fills the gap of impunity that judicial proceedings alone may not address, by removing individuals whose actions do not reach the threshold of criminal conviction but nevertheless undermine public trust and erode the legitimacy of the democratic state.

The ethical dimension of administrative dismissal extends beyond legal obligations to encompass fundamental duties toward victims and the broader project of social reconciliation. For millions of victims, the continued presence of those implicated in crimes within state institutions is a daily and painful reminder of injustice, perpetuating what transitional justice scholars call “secondary abuse.” This situation fuels feelings of pain and anger and clearly demonstrates that the victims’ suffering has not been adequately acknowledged. In contrast, the administrative dismissal of these individuals constitutes both symbolic and practical redress, representing official recognition of the victims’ suffering, a restoration of their dignity, and an affirmation of their status as citizens with rights.

The link between institutional reform and building social peace lies in preventing cycles of revenge and restoring public trust in state institutions. When authorities fail to remove or hold accountable known perpetrators, a dangerous vacuum emerges in the justice system, opening the door to individual acts of revenge and paving the way for new cycles of violence that threaten stability and undermine prospects for national reconciliation. Conversely, a systematic and transparent vetting process is a fundamental tool for peacebuilding, demonstrating to society that no one is above the law and dismantling the culture of impunity fostered by previous regimes.

Therefore, institutional reform should be understood as organically intertwined with the dignity and needs of victims. Recognizing the suffering, by removing perpetrators from positions of power, is a necessary step to restoring trust and legitimacy in the public sector. This approach acknowledges that transitional justice cannot succeed if it maintains the human structures that enabled the violations, as this sends contradictory messages about a lack of rupture with the past and threatens the transitional project by preserving the very structures that allowed the atrocities to occur.